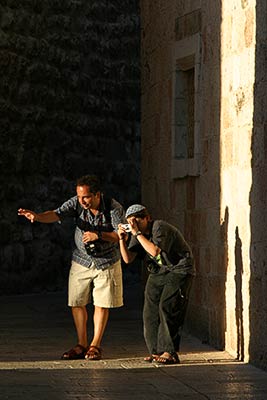

I arrived in Jerusalem armed with twenty-four Canon point-and-shoot cameras and 250 rolls of Kodak film. It was my first trip to Israel and I spoke neither Arabic nor Hebrew. I wandered the Old City's Muslim quarter hoping to find twenty-four potential students for a series of photography classes. I carried a letter written for me in Arabic inviting kids to a free photo class in the local community center. I also made friends with an enthusiastic and talented local photographer named Jonathan Weitzman, who worked with me throughout most of the project.

A few days later, some forty screaming Arab kids showed up for the first class, shouting in a language that I could not understand, banging on the door, and creating a whirlwind of chaos. I learned later that a rumor had started, that there was an American (me) giving away free digital cameras. When the kids found out that the cameras were not digital, and that the free film cameras had already been given out, some of them threatened to burn down the community center and in the days that followed a few windows were broken. After this incident, I was informed that we could no longer teach inside the center and had to hold class outside in a sun-baked courtyard.

The twelve Jewish kids, chosen by their community center, were placid in comparison. All that the two classes had in common was that each kid not stop popping the bubble wrap in which the cameras were packed.

I was new to the Middle East and knew little about the conflict. A fellow photographer from Magnum Photos suggested that I take a short trip to the outskirts of Jerusalem to see the barrier wall being constructed there. As soon as I did, I knew there was no way that classes could be held with Arabs and Jews together.

My trip and the classes were supported by Kids with Cameras, a non-profit organization started by Zana Briski. She had taught photography to the children of prostitutes in Calcutta, with the idea of empowering them through photography. This project in Israel was the second in a series. But instead of taking place in a community that was marginalized economically, as in Calcutta, Jerusalem was divided politically and culturally. The goal of the project was to make a portrait of Jerusalem from each side of the divide.

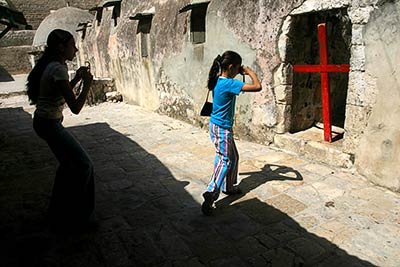

I gave each class a set of rules along with suggestions for taking better pictures. The first thing was to get them to stop taking pictures of their friends in various poses, and to get out and explore Jerusalem. Classes met twice a week in their respective quarters of the city. Jerusalem is made up of four quarters: Muslim, Jewish, Christian, and Armenian. The kids ranged from eight to twelve years old. An individual photo album was kept for each student, with the best photos. I did not hide from each class the fact that I was teaching both Arabs and Jews, but I was careful not to pit one group against the other, for fear that they might pull out. I thought that in time they might come to learn about each other, and that if they were interested in seeing each other's photos we could arrange a meeting.

One hot day Jonathan and I decided to take the Jewish class outside to a common rooftop area that straddles both the Muslim and Jewish quarters. It's a place where both Jews and Arabs seem to tolerate each other's close proximity. A few of the Arab students lived close by. As I showed the class some photos taken by Zvi, one of the best students, I heard our names shouted from far off: "Mr. Jason, Mr. John." In the distance was one of the Arab girls, little ten year old Isra, inching her way towards us. She was shocked that I was teaching Jewish kids. She was intensely interested, but at the same time afraid to come near. Isra decided to brave the big gap between her house and the place where we were sitting, and was immediately surrounded by the Jewish students. She was looking at their photos when some not so nice words in Arabic were exchanged between them. Then she tugged on my arm, trying to get me to take her back over the divide to safety near her home. She was afraid that once she turned her back on them, the Jewish kids would chase her. The noise alerted some of the other Arab kids and a confrontation was barely avoided as we called back the Jewish kids, who had started to chase her, telling them that class was over for the day. We had seen numerous little conflicts on the roof in weeks past. An hour later, Jonathan and I returned to the roof and showed photos taken by the Jewish kids to Isra and Raneen, the oldest Arab girl in the class and the best photographer. At first the two girls slapped the photos, which they didn't like, because they were taken by Jews, but after a while they commented with the few English words they knew, "Good; no good," and then another slap. Some days later, when I showed photos taken by Arabs to the Jewish class, the Jewish girls made a spitting sound at sight of the photos. But after these initial reactions, each side was fascinated by the photos of their counter-parts and by the culture that was so close to them but which they did not understand.

The Arab class was difficult to control even on good days. The translators who we hired failed to show, and we were left with screaming kids whose mantra became, "Give me camera, give me film." Luckily, we had Raneen, our star Arab student, who spoke enough English to quell the chaos. The kids gave me their shot film with their names on little pieces of paper squeezed into the hole on top of the film canister. We sometimes received crushed film from a frustrated Isra, and Wala, another Arab student, would open the back of her camera with unused film still in it, just to get a new roll. We taught them by putting the good photos in their individual photo albums, and giving them back the bad photos. I maintained the albums, and they often asked to see them. Once, when I was tired of seeing pictures of their friends, I crossed out some of Wala's photos with a marker and returned them to her. She was so upset that she tore them up and threw them in the air. But she learned her lesson and respected me more from that moment on. I realized that each kid just needed some special attention and would blossom, especially Isra, who always had a sour and sad face until I told her that she was the bravest photographer, and who was then transformed.

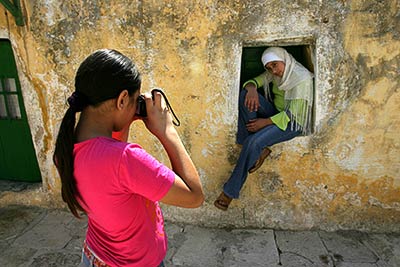

I started to do the same thing with the Jewish class, some of whom admitted late in the course that they really had no desire to be little photo-journalists but only wanted to add photos of their friends to their family albums. When we praised their individual albums and showed them some special attention they became more enthusiastic. While the Arabs seemed more emotional and impulsive in their picture-taking, as when Isra hit a priest on the shoulder in order to slow him down while she took his picture, and wasted a lot of film, the Jewish kids were able to sit quietly and absorb photo-concepts such as foreground/background, composition, and light. They were less inclined to take pictures of strangers. When I commented to Hodaya, one of the Jewish girls, that her picture might have been better if she had waited for a person to pass by and be in it, she replied that she had been waiting for a person to leave before she clicked the shutter.

We sometimes went on little excursions in the Old City with the Arab class because they had more free time. They liked going into churches. But not every kid showed up for each class. Once I saw a despondent Ala-Salami, one of the boys, trying to sell postcards at a time when there were no tourists around because of travel warnings from abroad. He sometimes braves the road that goes through the Jewish quarter outside the city gates to David's Tomb, where there are more tourists. When he showed up in class with a bandaged arm he said that some kids had set a dog on him. Some days later, he asked Jonathan and me if we wanted to go to David's Tomb, and I think he mostly wanted an escort. I later saw a Jewish kid try to trip him as he walked.

We had more contact with the Arab kids on a daily basis while walking through the Old City. The Jewish kids were less visible, mostly because they were confined to the Jewish quarter for security reasons since the start of the second Intifida. Zvi, one of the best Jewish students, lives in the heart of the Muslim quarter. On one Sunday, he was the only one to show up for class, and Jonathan and I decided to walk with him back to his house. We saw how he moved swiftly through the labyrinth of left and right turns, not staying too long in any one place. We ended up in an Arab courtyard and quickly went into his house and up to the roof for a view of the Old City. There are about sixty-five Jewish families living in the Muslim quarter. Zvi took a few pictures of the Dome of the Rock through some chicken wire. Then we headed down to the street and eventually arrived at the Petra Hostel, where I stayed in the Christian quarter and where the rooftop has one of the best vantage points for seeing the Old City, with its very colorful picture-puzzle of Jerusalem. But for Zvi, the one blue piece of that puzzle, the sapphire-colored mosque of the Dome of the Rock that stands out from the sand-colored and sun-bleached stones of the city, does not fit into the puzzle that makes up his world. He would want that piece replaced by the Third Temple, which prophesies say is to be rebuilt, fitting snuggly in its place.

One day the Arab class wanted to go on a little trip, and one of them suggested that we go to Abu Dis, the same place my photographer friend wanted me to see the barrier wall when I first arrived. It is only about fifteen minutes away, but once the kids were on board the bus they began to sing and clap as if they were going to a far-away summer camp. When we got off the bus we walked along the Israeli side. Some had not seen the wall this close up. A bond seemed to form between us on the bus that day, amid the chaos of the photo outing and the ice cream that followed, as we headed back to the city for falafel.

Summer was coming to an end and we had our last classes for the season. The Arab children earnestly asked for official diplomas as they were leaving, but we gave them Kids with Cameras t-shirts instead. Later that day, we set up a meeting with the two best students from each class so that they could see each other's work. They were Raneen and Zvi, each the oldest and the most talented in class. As the hot afternoon sky turned a soft gold we went up to the roof, which was to be the rendezvous point. Raneen showed up first, with a few of her classmates tagging along. I remembered that it was Raneen's birthday and brought her a t-shirt of her favorite Egyptian singing star. We were all nervous that Zvi might turn back when he saw that he was outnumbered. It turned out that one of his main concerns was whether Raneen would be taller than he was. They sat on either side of me and we opened their albums. Little Isra, who had been so scared to come close to the Jewish class a week before, came near and bravely slapped Zvi's foot, but he stayed calm. Fahti had a piece of gas pipe in his hand, on the ready, until Jonathan told him that Zvi was our friend, and then Fathi sat next to Zvi and shook his hand. Raneen said "This is beautiful, this is very beautiful" about Zvi's photos, and Zvi admitted that he liked her photos as well. The meeting lasted only a few minutes; soon the sun went behind a hill and we all went home to rest. The next day was a school day. Not long after, I went back to New York.

Months passed, and I returned to Jerusalem. It was mid-January and it rained for three weeks. My corner room at the Petra Hostel had a leak and there were small pools of water in the dips in the cold tile floor. I put rolled up blankets in front of the windows in order to block the incoming cold air and to soak up the moisture. I had been warned that Jerusalem had a winter season, and that as in most places people stayed indoors on cold and rainy days and that the kids would not be outside as they had been in summer. At the Petra we huddled around the stove to keep warm, as there was no heat in the rooms. And like always, an endless stream of tourists, backpackers, and dreamers came and went. Only the very religious, who were seeking some other kind of truth, stayed on, and they would often eventually find menial jobs at the hostel as a way to sustain themselves.

Months passed, and I returned to Jerusalem. It was mid-January and it rained for three weeks. My corner room at the Petra Hostel had a leak and there were small pools of water in the dips in the cold tile floor. I put rolled up blankets in front of the windows in order to block the incoming cold air and to soak up the moisture. I had been warned that Jerusalem had a winter season, and that as in most places people stayed indoors on cold and rainy days and that the kids would not be outside as they had been in summer. At the Petra we huddled around the stove to keep warm, as there was no heat in the rooms. And like always, an endless stream of tourists, backpackers, and dreamers came and went. Only the very religious, who were seeking some other kind of truth, stayed on, and they would often eventually find menial jobs at the hostel as a way to sustain themselves.

I met with the kids and showed them their photos in a slide show on my laptop, and also in an Israeli photo magazine called Contact that ran them. The Arabs slapped the Jewish photos when they saw them in the magazine, and when I showed the slides to four Jewish kids from the class the girls in the group made a spitting sound that I didn't think could come from them. One of them, Anat, who was helping me because Jonathan was now based in Gaza, didn't want to repeat to me what they were saying. So here I was, back teaching again, except that the tables had turned and now the Arab kids were less enthusiastic about coming to class, while the Jewish kids who had at first been hesitant about taking photos were now happily snapping away. But I could hardly call it a class because we now had to meet on the street in front of the Martin Luther Center. Isra had started going to school in a suburb outside the city and showed up only once in two months. Wala complained that she had lost her camera. Izak promised to shoot, but only took film and never shot any photos. Only Zuhir and Khalid came a bit more regularly. After much begging, I did buy Wala a new camera, but in the weeks that followed she gave me very little shot film. It was hard to find the kids; even though I would stop by their houses and they would promise to come, most never did. I was most disappointed that Raneen never showed up again.

It was easier to gather the Jewish kids together, since class was hosted by the Jewish Center and Pnina, the director, put out word that I was back, and they came. This time around, I met with the kids only once a week, mainly because they had to go to school. And I wanted to get out of Jerusalem every now and then. They were more enthusiastic this time, as a photo class was a respite from their studies and an opportunity to hooliganize. They did shoot, and they delivered spent rolls of film to me at every class. The weeks went by. I developed their film each week and showed them the results at the next class. I kept the good photos and created new albums to replace albums that had been lost by the airline on my previous flight back to New York. We scheduled the last class for just after Purim in March, when I hoped they would take photos of their holiday celebrations.

This time I printed out special diplomas, because I remembered how Isra had asked for one earlier, and I wanted some way to bring the class to an official end. But only a few of the Arab kids came to the last class, and I had to leave their diplomas with Raneen's family. Only Zuhir and Ala-Salami received theirs in person. The Jewish class had a warmer ending; everyone thanked me and received their diplomas as well.

In the end, all the kids were brought together by participating in the same project and by viewing each other's work, even if they could rarely be in the same physical space. I hope that later on some of the kids will remember taking these photos, and then will try to imagine, even if for just a moment, how the world is viewed by the kids in the other group. If they do, then at least in a small way, photography will have helped bridge the divide that separates them.

I still hope to return to Jerusalem in summer 2008, and to make a special evening in the yard of the Martin Luther Center, inviting all the kids and their parents, along with the mayor of Jerusalem, in order to show the photos on a big screen in the open air. The kids will each receive a book documenting the project, which they can take home to show their friends and, perhaps, one day show to their own children.

Director: Jason Eskenazi

jasoneskenazi@hotmail.com

jasoneskenazi@hotmail.com